As I Skyped with family members in Florida and California to share that I had successfully defended my dissertation on World War II-era family separation in the USSR, I appreciated how unfathomable the predicament my historical actors faced – completely losing contact with family members – is to us today. Even as a global crisis compels us to remain at home and limit our interaction with our closest relatives, a panoply of technologies allows us to have virtual movie nights, happy hours, and Passover and Easter celebrations with them.

Soviet citizens caught up in the upheavals of the Second World War were not as fortunate. The Nazi invasion of the USSR in June 1941 uprooted them from their homes as millions were mobilized to serve on the front, evacuated into the Soviet interior, and forcibly displaced to the Third Reich by Nazi forces. Due to this mass displacement, many Soviet citizens completely lost contact with their family members and experienced the conflict as a trial of family separation and uncertainty concerning their relatives’ fate. This state of uncertainty was often temporary; it was resolved with receipt of the news of relatives’ whereabouts or of their death. Yet my research reveals that for tens of thousands of Soviet citizens, wartime family separation was a protracted ordeal. Many struggled for decades to find missing family members, long after the war itself had come to an end.

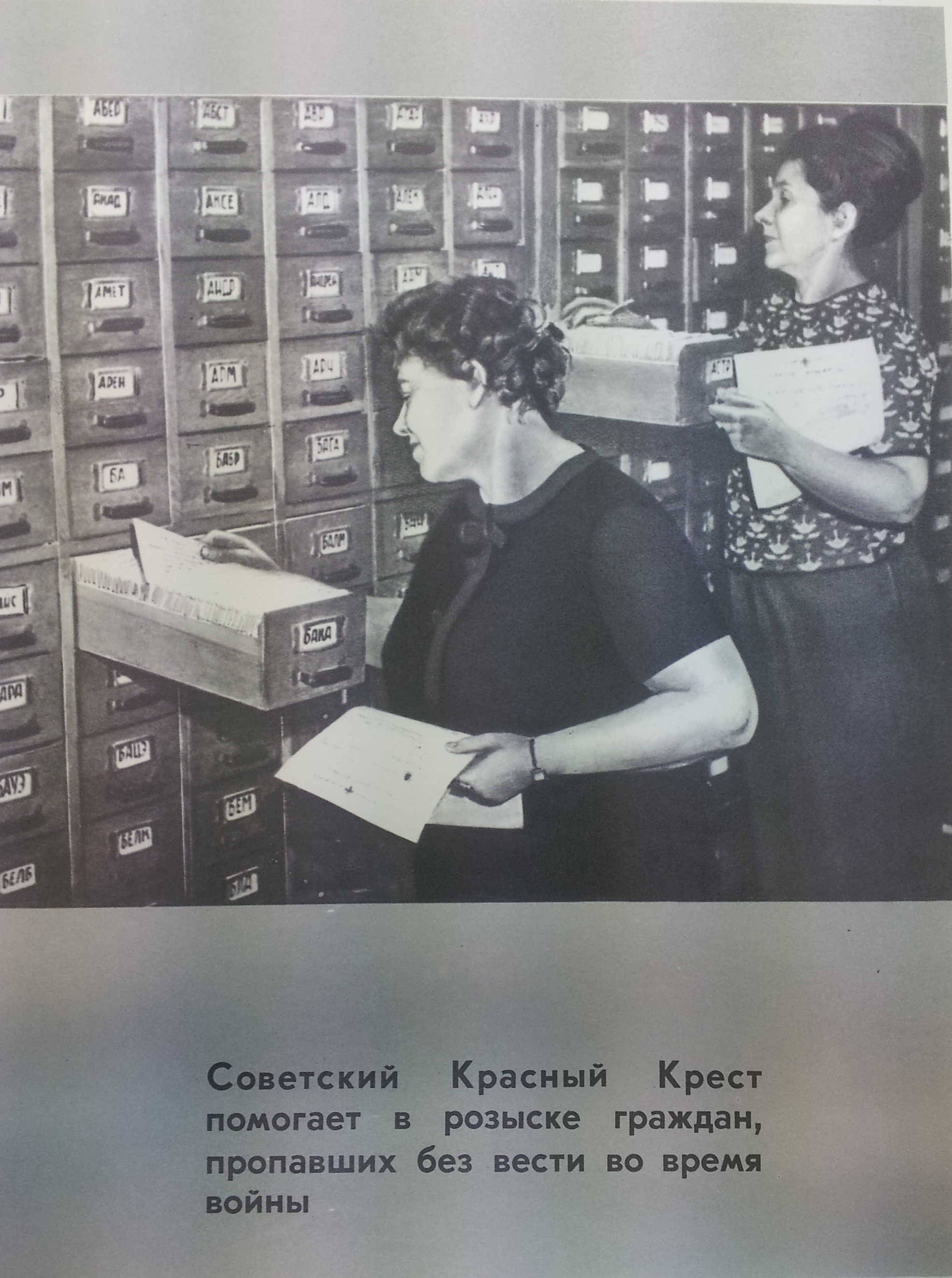

My research explores how, in an age before cell phones and social media, Soviet citizens tried to find family members lost in war. While some sought their relatives through informal networks of distant family members, friends, and acquaintances, many appealed to the Soviet regime for assistance to locate missing kin. In the midst of extensive wartime devastation – the conflict ultimately left approximately 27 million Soviet citizens dead and 25 million homeless – Soviet authorities managed to help war-torn families. The Kremlin established a wartime radio program dedicated to helping evacuees in the Soviet interior and military personnel at the front re-establish contact with family members. Soviet authorities also established a wartime tracing bureau which collected data on over 7 million evacuees, received tracing inquiries concerning 17 million citizens from 1941 to 1947, and established the whereabouts of over 3 million of them.

The USSR thus managed to marshal its pre-war surveillance and propaganda infrastructure to help citizens find family members lost in war. Yet, my research reveals that once the war was over, the Kremlin ultimately prioritized reuniting displaced Soviet citizens with overarching Soviet society, rather than with their biological relatives. While recent research has illuminated how Western and Central European officials endeavored to reunite biological families to rehabilitate war-devastated nations, the Kremlin focused on reconstituting war-fractured Soviet society. It also championed that a shared Soviet identity could supersede the kinship ties torn asunder by the conflict and thereby suggested that the ideal Soviet family was not necessarily tied by blood, but bound by a shared commitment to the Soviet Motherland.

Despite the Kremlin’s assurances that overarching Soviet society could replace lost kin, Soviet citizens persisted in their efforts to find lost family members in the decades after the war’s end. Due to their dogged efforts and the advocacy of a renowned children’s poet Agniia Barto, a novel radio program, To Find a Person, was established in 1965 to help wartime orphans in their 20s and 30s trace any of their surviving family members. As many of them lost their family when they were young children and did not remember their basic biographical information, such as their birthplace and birthdate, their parents’ names, and even their own names, the program broadcast their distinctive childhood memories which had the potential to be recognized by surviving relatives. While many wartime orphans remembered their relatives and longed to be reunited with them, others sought surviving kin in order to “find themselves,” uncover their family origins, and determine their proper place in Soviet society.

The persistent search for relatives in the decades after the war suggests that many Soviet citizens believed that kinship ties were in fact the ties that bind. Yet over the course of my research, I have found some evidence that the official idealization of a supranational Soviet identity may have actually helped citizens cope with the devastating wartime losses. I plan to conduct further research to better understand the gamut of popular responses to the Kremlin’s idealization of “the great Soviet family” in a postwar landscape dominated by families irrevocably broken by total war.