Author: Kristen de Groot

Full text at Penn Today

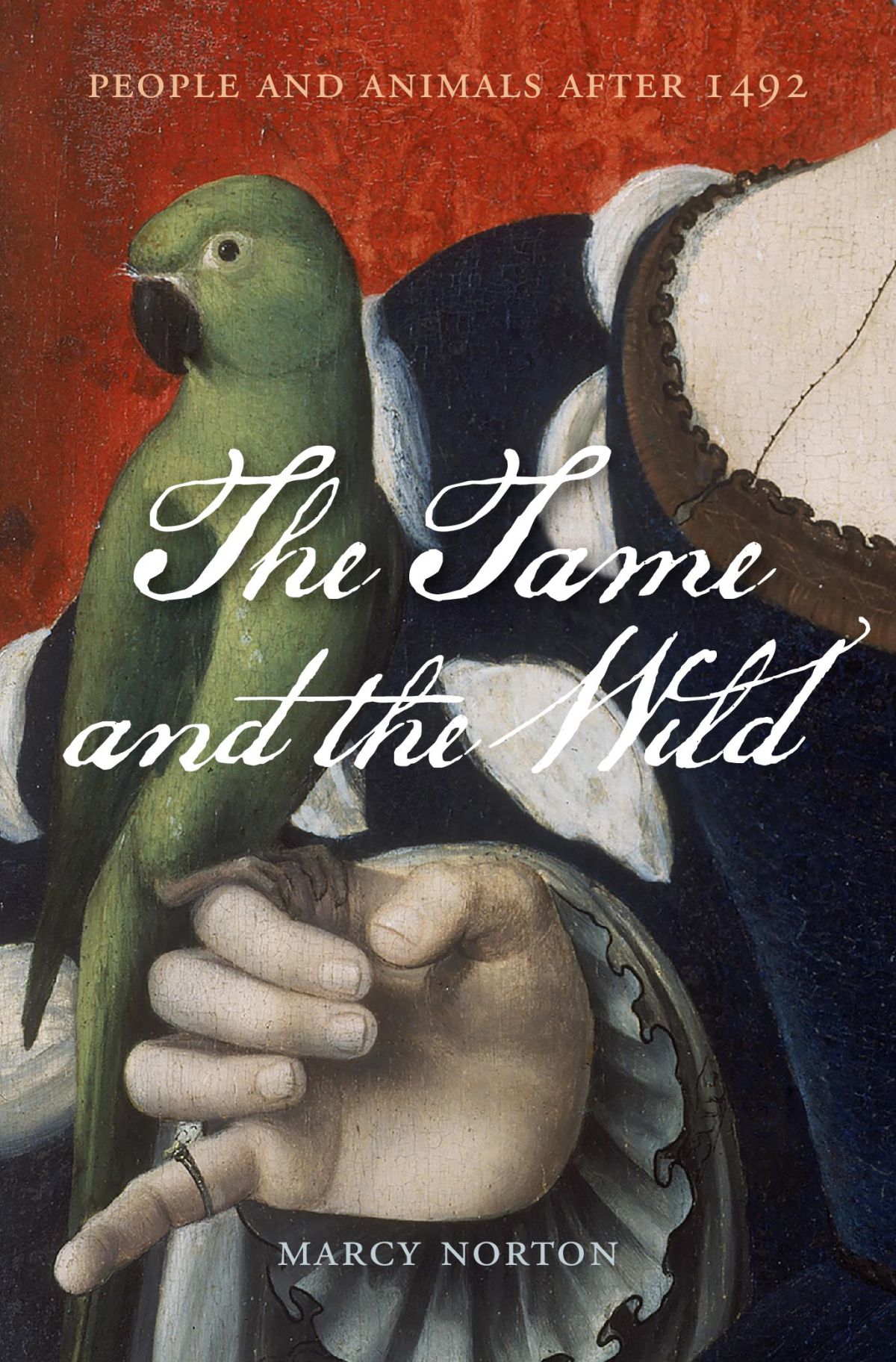

Marcy Norton of the School of Arts & Sciences uses history as a tool to understand what’s happening in the present. Her new book “The Tame and the Wild, People and Animals After 1492” does just that by looking at how European and Native American relationships with nonhuman animals differed and became entangled in the Atlantic World.

Animals played a huge role in colonization, from the horses who served in military campaigns and the dogs deployed as instruments of terror, to the livestock animals who made possible the agropastoral economy that facilitated the dispossession of Native people’s labor, land, and even lives.

Yet despite this colonial violence, Indigenous communities maintained their traditional ways of interacting with nonhuman animals, says Norton, associate professor of history. In the Caribbean, lowland South America, and Mexico, Indigenous people not only hunted wild animals for food but also selected some to raise as companion species. Parrots and monkeys were commonly chosen to be tamed (also known as familiarization), but almost any kind of animal was eligible.

The book explains how these differences in approaching animals transformed societies on both sides of the Atlantic, even paving the way for zoological science and the modern pet.

Penn Today spoke with Norton about how she landed on the topic, memorable anecdotes from her research, and what lessons we can draw from the past about the current state of animals in the world.

Your previous book ‘Sacred Gifts, Profane Pleasures’ looked at the history of chocolate and tobacco in the Atlantic world. How did you come to explore this topic about animals in the colonized Americas?

As a historian, I’m always driven to use history to understand what’s going on currently. In terms of animals, the paradox that many of us are aware of is we have pets like dogs and cats that are cherished family members and give us so much pleasure, and on the other hand we live in a world where nonhuman animals are suffering more than ever before as a result of factory farming, climate change, and environmental pollution. I wanted to know how to make sense of this paradox. For me, the early modern period is always a good place to look because on the one hand it can feel very remote, but on the other hand many of our practices and ideas originated there.

My first book looked at tobacco and chocolate as Indigenous technologies that went back to Europe and had enormous influence. I have a longstanding interest in the intersection between Indigenous and European communities and mutual influences on their cultures.

In doing research for that first book, I came across some fascinating material about nonhuman animals. One source described the experiences of an Indigenous man in the early 16th century in what is today the Dominican Republic. He had fled Spanish exploitation and was living autonomously in a region outside Spanish control and survived, in part, through a relationship that he forged with three feral pigs that he trained to act like hunting dogs to hunt other pigs.

When some Spanish soldiers arrived in the area and killed the pigs, the man was completely bereft. He described how they had provided company for each other, and he’d given them names. For this man, the feral pigs belonged to the same category as all wild animals: they could be potentially hunted for food or tamed to become companions. He was, I believe, also influenced by the European practice of using dogs to hunt wild animals. The story comes to us through a Spanish chronicler who was baffled that a person could collaborate with and cherish pigs in this way. From his European perspective, the man’s relationship with the animals would have made perfect sense if they were dogs, but for the Spaniard pigs were ‘livestock,’ objects rather than subjects.

We still see these kinds of stories today, like the recent one where a little girl participating in 4-H withdrew her beloved goat from auction and then was sued and forced to surrender the animal, who was then slaughtered. This insistence that certain animals are nothing more than livestock has very deep roots. Yet, as we can see from the man who cultivated a relationship with the pigs, people in the past also had other ways to understand these animals.

Why is this different way of viewing nonhuman animals important to examine at this particular point in time?

We know that our present way of interacting with animals is literally unsustainable, when you think of the role that livestock production has in climate change, groundwater pollution, and habitat degradation. That’s just on the environmental level. On a social justice level, the mistreatment of stifling confinement and early slaughter that is inflicted on our fellow creatures is horrendous. For a lot of people, there’s the sense of ‘well, that’s just how it has to be, it’s just the way things are and it’s too bad.’ One of the most powerful things that history can do, especially when we look at a diversity of social arrangements, is that it liberates the imagination.

I have a chapter that looks at how Indigenous groups reacted to livestock husbandry. Many were really interested in chickens, an animal brought by European settlers. But I found many examples where Native people treated chickens just as they treated wild animals chosen for taming: they fed them in order to make them companions. If you fed another animal, you made them part of your family. European observers found it very strange that Native people would have chickens living with them but not eating them or even their eggs. But from the Indigenous perspective, the idea that you would feed a chicken and then eat the chicken was revolting.

When you put animal livestock husbandry in this broader time range and cultural range, and intentionally estrange yourself from it by looking at it through, for example, early modern Indigenous eyes and see how repugnant it was for them, it frees up our powers of imagination, seeing that things have been otherwise and can be otherwise.

There’s this idea that animal domestication, leading to livestock husbandry, is a necessary milestone of human progress. And so for a long time scholars viewed Indigenous societies as primitive or inferior if they ‘failed’ to domesticate animals. Once you take away the framework of a hierarchy of civilizations and instead look at the diversity of ways people have interacted with nonhuman animals, new possibilities can unfold.

What are you hoping readers take away from this book?

I hope they start to question the assumption that animal domestication of a certain type is a necessary stage in human advancement. I hope it makes them curious about the different kinds of arrangements that could be possible. You can see so many more possibilities when you aren’t going in with an assumption that the way things developed in the West is the only way they could have and should have developed.