Full text and images at OMNIA

Writer: Susan Ahlborn

Children of Freedom

In the late 1700s, New York and four other northern states passed laws that freed children born to enslaved women. Historian Sarah Gronningsater wanted to know more about how this extraordinary situation affected those children. A former high school teacher, she’s always been interested in how young people make their way in the world and grow to understand their adult purpose.

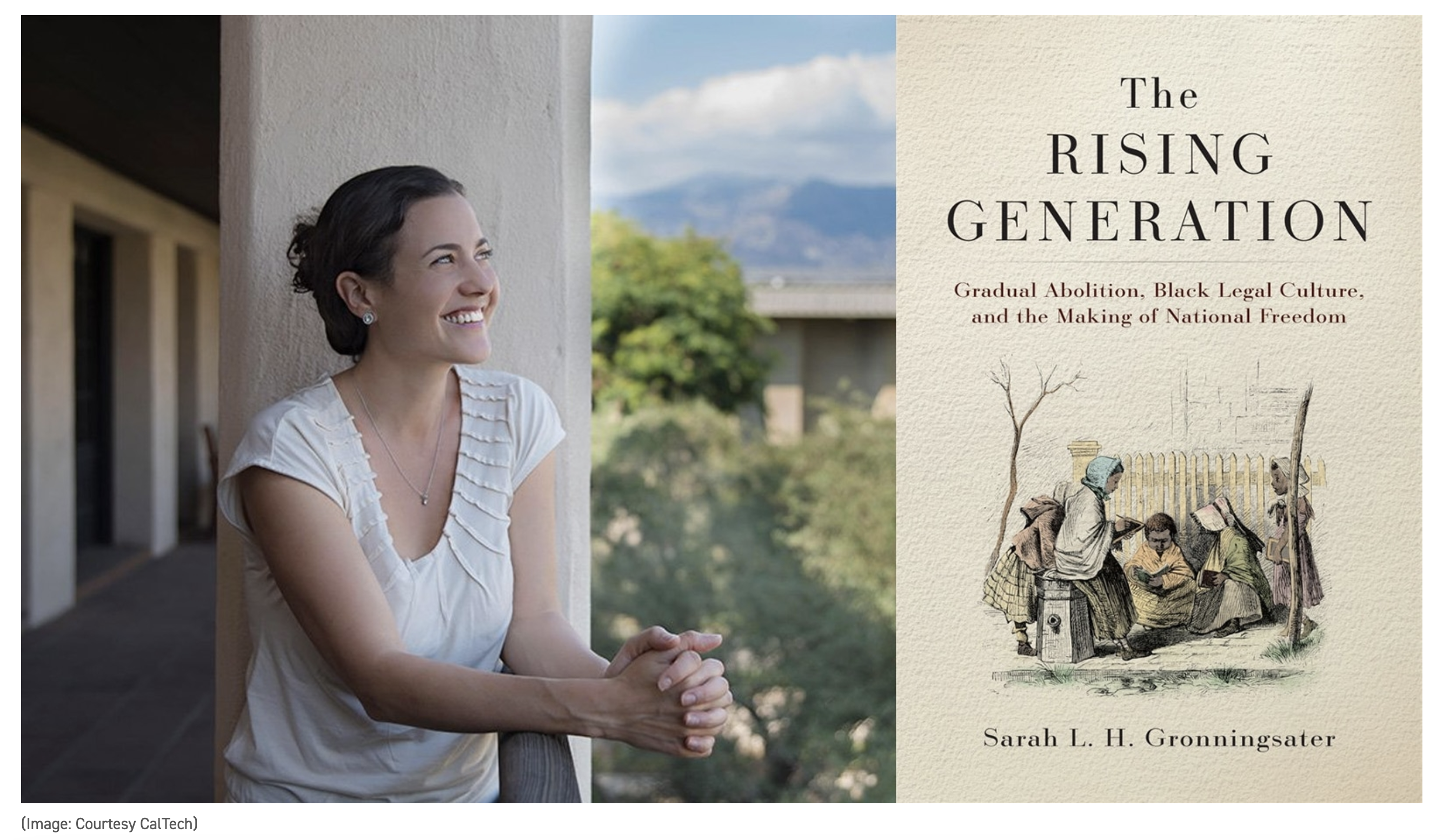

Gronningsater concentrated on New York, the most economically and politically powerful northern state in the young nation, spending years seeking out published and unpublished sources. That effort resulted in her book, The Rising Generation: Gradual Abolition, Black Legal Culture, and the Making of National Freedom. It tells the story of how Black people—both enslaved and free—found ways to protect and nurture these children using the laws and politics of their state, and how “this rising generation” of children eventually changed the United States itself.

Liberty for All

The American Revolution energized the abolition movement in the United States during and after the war. Particularly in the North, Quakers, anti-slavery patriots, legislative representatives, lawyers, and ministers began proposing ways they might eliminate slavery. At the same time, Black people who had escaped enslavement were speaking out in sermons and speeches or helping others maneuver out of bondage.

All of this was happening as the colonies were becoming states, setting up their constitutions, and writing new laws in their independent legislatures. “It’s a moment of opening when the winning patriots get to decide what laws they are going to have in these new states in this new country,” says Gronningsater, an assistant professor in the Department of History.

However, the abolitionist sentiment conflicted with another revolutionary ideal: property rights. New York and several other northern states were unwilling to free enslaved people outright. Instead, they passed gradual abolition laws declaring that children born to enslaved mothers after a certain date would be born free. At the same time, these laws also decreed that the children would labor as servants for their mothers’ masters until adulthood.

“It’s borrowing a lot from English poor law systems where poor children could be drafted into forced labor,” Gronningsater explains. “These Black children got slotted into that legal category. It was a pretty weak version of freedom at first. But it was also a move away from lifelong slavery.”

A Mandatory Education

Abolitionists recognized that the free children would need an education. “To maintain a healthy republic, you need strong citizens,” Gronningsater says. “The most liberal of the white abolitionists really believed that these children born to enslaved mothers, if they could be raised to be ‘good, liberty-loving citizens’ and given an education, would one day become excellent American adult citizens.” Black parents and mentors also poured their resources in this generation’s education.

New York State passed a law that required the children to be taught to read and write. It had teeth: Those who did not receive education would be freed earlier. “The free Black and enslaved population learn this and start going to courts, to lawyers, to local town officials and saying, ‘I was supposed to be educated and it didn’t happen, and so I should be free early,’” Gronningsater says.

That spurred other efforts to free those who were still enslaved. “You’ll see people working extra hours to free members of their family, to buy children out of servitude, to buy slaves out of their lifetime bondage,” says Gronningsater. Some Black families started businesses. Others earned enough to buy land that they could use to generate even modest capital; that went toward freeing additional family members, she adds. “A lot of the freedom that actually happens is from the efforts and politics and knowledge” of the Black community itself.

An elite white abolitionist group led by John Jay created the African Free School in New York City, one of the nation’s earliest public schools. By the 1820s it had expanded to six buildings and had both Black and white teachers. The school also offered free classes at night for adults.

Other schools formed throughout the state, some built by Black families. Advertisements and records of fundraisers for these schools—events at the local church that included poetry readings or speeches by the children, for example—offered examples of children’s voices. More than that, according to Gronningsater, they displayed the community’s mission, explicitly saying that these children would have advantages that their forebears didn’t.

The history of abolition in the North is not as well known, and I wanted to show how seriously the Black population across New York State took their newfound free citizenship. The story of 19th-century democracy and party politics writ large, to me, has to also be a story of these free Black people in the American North.

“This was a generation born in a new optimism and hope,” she says. “They were raised surrounded by the belief that they would grow up and help further expand freedom nationwide. They took that message really seriously.”

Raising Their Voices

The result of this work and conviction, says Gronningsater, was a remarkable number of Black abolitionists both famous and less known, men and women alike, who, by the 1850s, were running the Underground Railroad, leading Black churches, editing Black newspapers, petitioning governors and legislatures, and helping to fund court cases. Along with their parents, both enslaved and free, these children grew up to become political actors, working with local and state officials for stronger anti-slavery laws.

When Abraham Lincoln finally issued the Emancipation Proclamation in 1863, “Black abolitionists are loud and clear about what they want freedom to look like,” Gronningsater says. “They start writing Congressmen. They work every connection they have. They argue passionately in newspaper editorials, they create interstate equal rights leagues with free Black people from across the North, and they start pushing the Federal government to create a situation in which equality before the law will be real.”

Jim Crow laws rolled back many of the achievements of the 1860s and ’70s, yet even so, this generation of Black Northerners made real progress. It’s a notion Gronningsater says she wants readers to understand. “The history of abolition in the North is not as well known, and I wanted to show how seriously the Black population across New York State took their newfound free citizenship,” she says. “The story of 19th-century democracy and party politics writ large, to me, has to also be a story of these free Black people in the American North.”